Over the many years that I have tutored children and teens in writing, and as a college essay coach, I’ve repeatedly heard parents say, “My kid is lazy; he doesn’t do his homework until it’s too late.” I’ve also heard parents say “My daughter always procrastinates until the last minute.” Let me just say, unequivocally, that the kid is NOT lazy. Procrastination, missing deadlines, not following through with tasks are common symptoms of ADHD.

Teens with ADHD typically experience some or all of the following:

- Distractibility and lack of focus

- Disorganization and forgetfulness

- Self-focused behavior

- Hyperactivity and fidgeting

- Heightened emotionality and rejection sensitive dysphoria

- Impulsivity and poor decision making

- Poor concentration and trouble finishing tasks

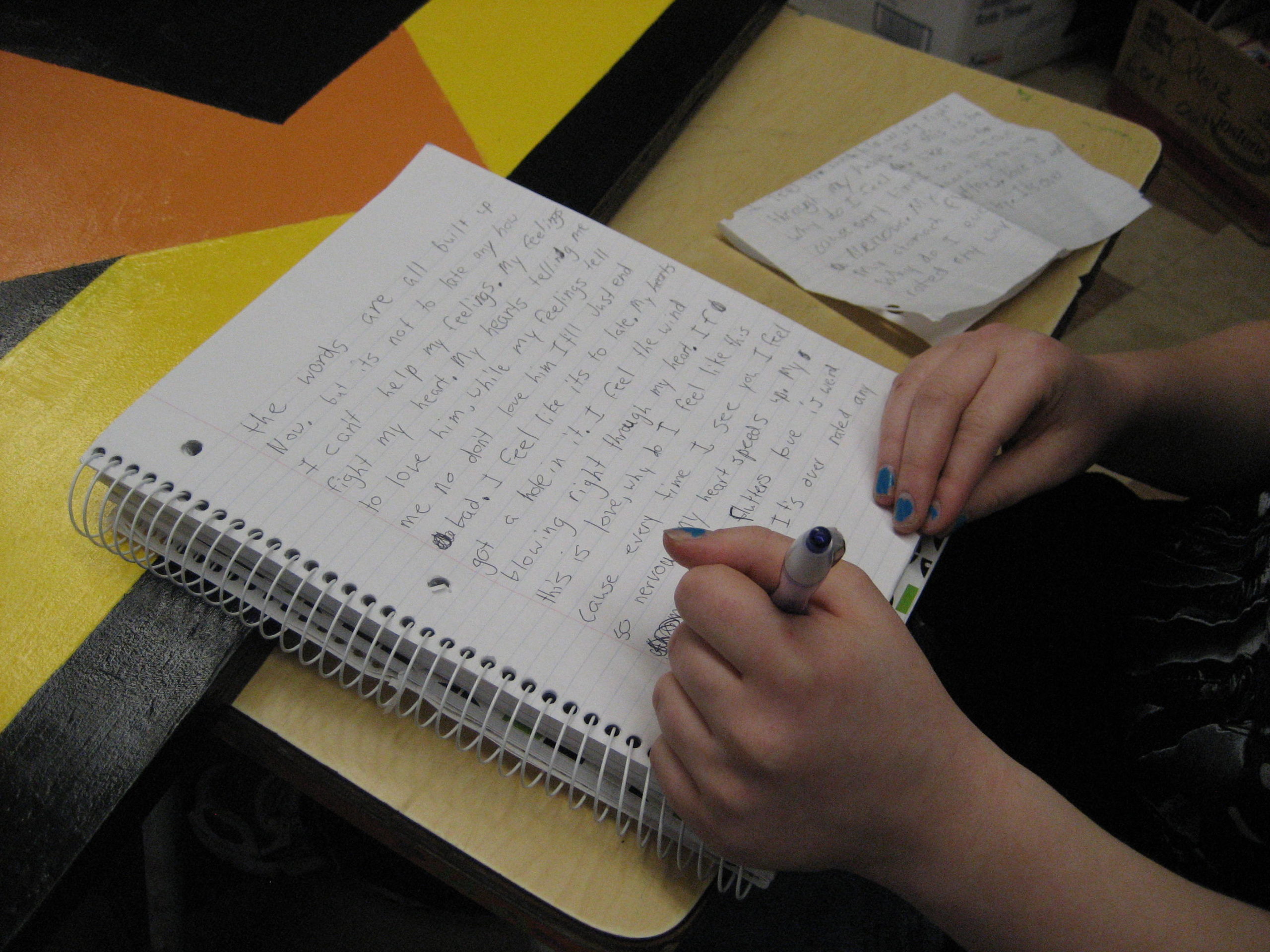

According to ADDitude, teens will have a few specific activities or tasks for which they have no difficulty in exercising their executive functions quite well, which can be a source of confusion among parents, physicians, and psychologists. This may be in playing a favorite sport or video games; it could be in making art or music or some other favorite pastime.

Experts say that 80 to 85 percent of preteens continue to experience symptoms into their adolescent years, and 60 percent of children with ADHD become adults with ADHD. The impact of ADHD symptoms may increase or decrease over time depending on the individual’s brain development and the specific challenges faced in school or at work.

Further, according to ADDitude, many of your teens’ problems at home, at school, and in social settings arise due to neurological delays. ADHD is tied to weak executive skills — the brain-based functions that help teens regulate behavior, recognize the need for guidance, set and achieve goals, balance desires with responsibilities, and learn to function independently.

How does this manifest in teens?

- Response inhibition (being able to stop an action when situations suddenly change)

- Working memory

- Emotional control

- Flexibility

- Sustained attention

- Task initiation

- Planning/prioritizing, organization

- Time management

- Goal-directed persistence (sticking with a task when it becomes “boring” or difficult)

- Metacognition (the awareness and understanding of your own thought processes a.k.a. self-awareness)

What can you, the parent , do? Don’t say “He’s lazy and will outgrow it” thus setting your child up for failure in college and beyond. If you see these symptoms, talk with your child’s doctor. ADHD is very treatable. The symptoms in teens are treated with medication, behavior therapy, and/or through changes to diet and nutritional supplements. Regular exercise and sufficient sleep are also very important.